Exhibition Introduction

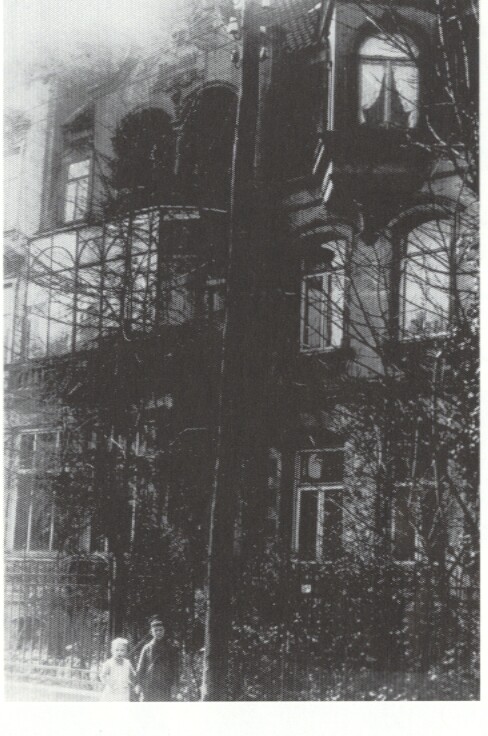

Photograph of Schwitters' house at

Photograph of Schwitters' house at Waldhausenstraße 5, Hannover

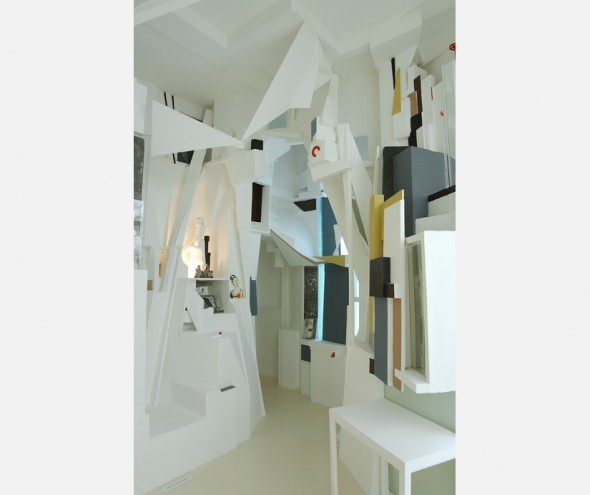

Reconstruction of the Merzbau in the

Reconstruction of the Merzbau in theSprengel Museum, Hannover

Kurt Schwitters’ Hannover Merzbau (1923-1937) represented the peak of Merz, Schwitters’ one-man style, movement, and artistic philosophy. This massive sculpture grew over the course of nearly two decades to encompass much of the interior of the artist’s home, evolving constantly until Schwitters was forced to abandon it. The work began as isolated sculptures (or columns) in Schwitters’ studio, which were eventually built upon and connected to form the immense piece. Relying on earlier scholars’ assertions of which photographs catalogue each stage in the Merzbau’s development, this exhibition explores how the photographs’ established chronology exhibits Schwitters’ increasing interest in cohesion, or merging the various works into a Gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art). Additionally, the Merzbau can be understood to encompass the aims for a “Merz stage” laid out in Schwitters’ 1920 essay “Merz,” particularly in its movement towards “the Merz composite work of art” and away from the disruptive style associated with the Berlin Dadaists. By visualizing the Merzbau’s development through its photographic evidence, one can see a departure from fragmentation towards a total work of art, the coveted goal of Schwitters outlined in “Merz.”

The name for Schwitters’ practice, Merz, reflects its Dada influence through its nature as a short, nonsensical word that served as a brand name and manifesto all in one. Likewise, the Hannover Merzbau began as an offshoot of Dada practices. The separate sculptures that served as the starting point of the Merzbau had much in common with those created by the Berlin Dadaists for the First International Dada Fair in 1920, and they indicate Schwitters’ keen interest in Dada practices during the early years of the Merzbau’s construction. In addition to their visual similarity, these early components of the Merzbau also demonstrate a conceptual link to their Berlin Dada counterparts. As sculptures that were not permanently tied to their location in Schwitters’ home, these works had the potential to be transported to a location where a wider audience could access them. As the Berlin Dadaists were concerned with disseminating their work to a wide audience, this potential mobility is starkly contrasted with the later Merzbau. Schwitters gradually tethered the work to its location, thereby inherently limiting its audience to those privileged with access to the artist’s home. Furthermore, Schwitters’ focus on fragmentation in the early sculptures speaks to its Berlin Dada influence. The sculptures are constructed as three-dimensional collages, built up by the fragments of found materials. This practice was central for the Berlin Dadaists, and in the “First German Dada Manifesto” Richard Huelsenbeck expressed the aim of borrowing varied fragments from life by stating “Life appears as a simultaneous muddle of noises, colors, and spiritual rhythms, which is taken unmodified into Dadaist art, with all the sensational screams and fevers of its restless everyday psyche and all its brutal reality.”

The Merzbau, a work perpetually in flux, evolved from this early stage of isolated statues to become a cohesive work. After Schwitters accumulated collaged objects, he began to cover them with a shell of plywood and plaster, molding geometric forms that were eventually painted white. While its core was made up of Dada works, its shell bore more relation to Expressionist and Constructivist works. This transition fulfilled the aims of Merz, which embraced the fusion of diverse artistic styles. According to Schwitters, it was Merz’s nature to observe connections in the world, and in this way the Merzbau served as the ultimate pinnacle of Merz as a project that literally connected the various artistic movements that Schwitters associated with. Schwitters laid out many of the aims of Merz in his 1920 essay “Merz.” In addition to identifying the character of Merz, this essay highlights Schwitters’ aim for the Merz stage. This can be understood as a Gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art) by Schwitters’ statement, “My aim is the Merz composite work of art, that embraces all branches of art in an artistic unit.” Several aspects of the foretold Merz stage echo the later realizations of the Merzbau project. For example, Schwitters indicates, “The parts of the set move and change, and the set lives its life.” This is true of the Merzbau, which grew and changed over the course of nearly two decades, continually reflecting the current influences in Schwitters’ career. Schwitters also concludes his prediction of the Merz stage by stating that “even people could be used” as its material, a phrase which is almost certainly connected to the future Merzbau. One of the Merzbau’s most fascinating characteristics was its literal inclusion of Schwitters’ artistic community. First-hand accounts by artists’ who encountered the Merzbau (such as Hans Richter) indicate that Schwitters dedicated niches of his project to artists that he admired, often including tokens from that person. For example, László Moholy Nagy was incorporated through the inclusion of a pair of his socks, and Richter through a lock of his hair. Other prominent modernists with grottos dedicated to them included Piet Mondrian, Hans Arp, Theo van Doesburg, Naum Gabo, El Lissitzky, Kazimir Malevich, and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe.

Schwitters even goes so far as to state that the Merz stage would be connected through wires and have its surfaces smoothed over, an idea that came to be reality as the Merzbau progressed. Perhaps the most interesting connection to the idea of the Gesamtkunstwerk is the title itself. The two great reoccurring symbols of the Gesamtkunstwerk were the cathedral and the theater. The first of these is already alluded to Schwitters’ alternate title for the Merzbau, The Cathedral of Erotic Misery. However, it is the second symbol, the theater, with which Schwitters identifies as his aim in the essay “Merz” in his quest for the Merz stage. This is significant. While the cathedral is typically associated with the fusion of plastic arts (painting, sculpture, architecture), the theater is linked to the synthesis of the temporal arts (poetry, music). Yet the very nature of the Gesamtkunstwerk resists such a division, and we are led to contemplate whether or not the plastic environments created to host temporal expressions can ever be fully complete without each other. For example, a church is created to host religious activity, and a music hall is constructed to provide a space for music. The plastic and the temporal can be appreciated separately, but reach a greater unity through their intended purpose. It is possible to view the Merzbau as an iteration of this greater synthesis. The plastic environment, the Cathedral of Erotic Misery, was the realization of the Merz stage, which Schwitters indicated in his essay “Merz,” “serves for the performance of the Merz drama.” This drama was Merz itself, the artistic practice and life philosophy of Schwitters, which played out on the stage of Schwitters’ home, the Merzbau.

The Merzbau progressed slowly away from its roots in the fragmented Berlin Dada aesthetic towards a unified piece, yet it never fully abandoned its Dada origins. Rather, these were swallowed by the all-encompassing aims of Merz, resulting in a work of art that celebrated chaos and order, fragmentation and unity. This was the total experience set out in “Merz,” and the realization of the coveted Merz stage.